Our local market – in the parallel street, six days a week – has a great fish stall, and during Lent it’s become even bigger, for obvious, traditional Christian diet-related reasons.

I love eating fish, but although I cook all the time, I’ve been fairly timid over my lifetime really embracing buying fresh fish and cooking it myself. The fish stall round the corner, however, is really motivating me, to try and cook more fish, to experiment, and to try and learn some of the innumerable Italian names for fish, both standard and dialect.

There are plenty of familiar species on the market, such as mackerel (sgombro), which offers one of the marginally less unethical choices in our era of overfishing. But there are also plenty of weird and wonderful species we don’t get in the UK, such as the stargazer (Uranoscopus scaber; pesce prete – priest fish).

I bought some stargazer without having a clue what it was, on the advice of the fishmonger (pescivendolo), and, through the miracle of Facebook, was able to use the groupmind to identify it.

When we bought some fish called cerino on the market, via Facebook again we were able to identify it as the slightly less exotic grey mullet. Cerino must be another dialect term, as the standard Italian term for grey mullet is cefalo, while another Lazio dialect name is mattarello (“rolling pin”).

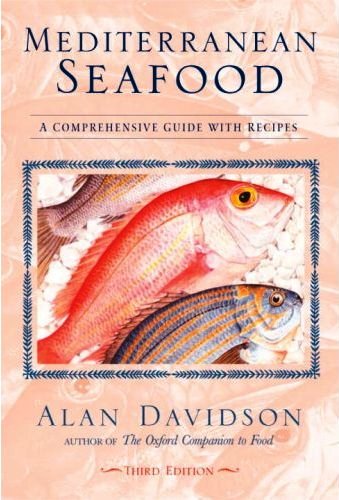

Such is my confusion that a friend of a friend on Facebook recommended I buy Alan Davidson’s book Mediterranean Seafood – in both English and Italian (called instead Il mare in pentola – The sea in a saucepan). The latter helpfully lists a lot of the Italian regional dialect names. Though not cerino.

Anyway, thank you very much photographer Mimi Mollica, a Sicilian who recommended the book and also gave us a recipe for fish stew and cous cous. Which I finally made today.

I’m going to try and blog the recipe in both English and Italian, which I’m learning, very slowly. Hence the Italian will probably be fairly crude for Italian speakers. Apologies in advance.

Proverò a mettere nel blog la ricetta del Pesce Stufato alla Siciliana in inglese e in italiano, che sto apprendendo molto lentamente. Il mio italiano sarà molto brutto per gli italiani e per le persone che parlano bene in italiano. Mi scuso in anticipo.

REVISIONE: La mia insegnante l’ha corretto. Grazie Clelia!

Anyway, Mimi recommends using firmer flesh, flavoursome fish like:

Comunque, Mimi suggerisce di usare un pesce con una polpa un po’ più dura e gustosa come:

| English / Inglese | Italian / Italiano | Italian dialect / dialetto* | Latin / Latino |

| Scorpion fish (red) | Scorfano rosso | Cappone (Toscano) | Scorpaena rossa |

| Scorpion fish (black) | Scorfano nero | Scorpaena nero | |

| Scorpion fish (small) | Scorfanotto | Scorpaena notata / ustulata | |

| Weever (greater) | Tracina drago | Trachinus draco | |

| Grouper (dusky) | Cernia | Zerola (Lazio) | Epinephelus guaza / Serranus gigas |

| Gurnard (tub, tub fish) | Capone gallinella | Capone panaricolo (Lazio) | Triglia hirundo / lucerna |

| Guarnard (red) | Capone coccio | Cappone imperiale (Lazio) | Aspitriglia cuculus / Triglia pini |

| Gurnard (grey) | Capone gurno | Gallinella (Tuscano) | Eutriglia gurnardus / Triglia malvus |

* Just a few, too many to mention!

Solo qualche, ce ne sono tanti!

And other fish, preferably sustainable varieties.

E altre pesce, preferibilmente di tipo sostenibile.

This isn’t a precise recipe – use your instincts with quantities.

Ask your fishmonger for enough fish for however many people you’re feeding.

I made it as a (large) meal for two, so I used:

Sauce

2 small-medium red scorpion fish

extra virgin olive oil

1 large white onion, coarsely chopped

2-3 cloves of garlic, peeled but left whole

White wine

500g fresh tomatoes, peeled (cut a cross in the skin, drop them in boiling water for about a minute, remove, peel) then coarsely chopped, or OR a tin of tomatoes

2-3 red chilies (depending on heat and your taste), de-seeded and chopped

salted capers, about a tablespoon, or more if you particularly like them

salt and pepper (freshly ground, naturally)

Soften the onions in a pan.

Add the garlic, and soften slightly.

Add the fish.

Increase the heat slightly and cook the fish, for about 4 minute each side.

Add a glass of white wine.

Increase the heat more, and cook off some of the alcohol.

Add the tomatoes, chilies, capers, more wine and water, to almost cover the fish.

Simmer until the fish is cooked, the flesh coming away from the bone.

Remove the fish.

Take the flesh off the fish.

Put the fish spine back in the sauce.

Simmer the sauce to thicken.

Remove the fish spine.

Put the fish flesh back in the sauce.

Season to taste.

Meanwhile, make the couscous.

200g ish couscous

1 small red onion, in thick slices

2 bay leaves

Extra virgin olive oil

salt and pepper

fresh parsley, coarsely chopped

Put the couscous in a bowl with a few bay leaves, the red onion, and some salt.

Pour over boiling water and a slosh of olive oil and cover.

Stand for 10 minutes, then check it’s softened enough. If not, pour over some more boiling water, and stir in. If it is, stir to break up any lumps.

Serve the couscous with the fish stew, sprinkled with parsley.

I expect my version isn’t exactly authentic (I’ve never even been to Sicilian, never mind actually eaten the real thing), but it was very tasty.

La ricetta in Italiano

Questa non è una ricetta preciso – usa i tuoi istinti con la quantità!

Chiedi al tuo pescivendolo per abbastanza pesce per le persone a tavola.

Ho fatto un pasto (grande) per due, con:

Stufato

2 scorfani piccola-medi, puliti

olio d’oliva extravergine

2-3 spicchi aglio, intero e puliti

1 cipolla bianca, grande, tritata grossa

Vino bianco

500gr pomodori, pelati, o una scatoletta di pomodori pelati

2-3 peperoncini (come si preferisce), senza semi, tritati

capperi salati, un cucchiaio da tavola o più

sale & pepe nero (macinato fresco)

Soffriggi la cipolla in una pentola.

Aggiungi gli spicchi di aglio, e soffrigi un po’.

Aggiungi i pesci.

Aumenti la fiamma un po’ e cuoci i pesci, per circa 4 minuti ogni lato.

Aggiungi un bicchiere di vino bianco.

Aumenta la fiamma, e stufa un po’ di più.

Aggiungi i pomodori, peperoncino, capperi, e abbastanza vino e acqua fino quasi a coprire i pesci.

Stufa a fuoco lento fino a quando la polpa dei pesci è morbida e sollevata delle lische.

Prendi i pesce.

Togli la polpa dei pesci.

Rimetti le lische più grande (spine) nel stufato.

Cuoci a fuoco lento per addensare.

Insaporisci con sale e pepe.

Nel frattempo, fai il couscous.

200gr (circa) couscous

1 cipolla rossa, piccola, affettata grossa

2 foglie d’alloro

olio d’oliva extravergine

sale & pepe nero (maccinato fresco)

prezzemolo, tritato grosso

Metti le fette di cipolla, le foglie d’alloro e un po’ di sale in una ciotola.

Copri tutto con acqua bollente, aggiungi un po’ d’olio d’oliva e coprila.

Lasciala per 10 minuti, poi verifica se il couscous è abbanstanza morbido. Se non lo è, aggiungi un po’ d’acqua bollente e mescola. Quando è pronto, mescola di nuovo per rompere qualche pezzo.

Servi il couscous con il stufato, cospargere con il prezzemolo.

Penso che la mia versione non è proprio autentica (non ho visitato la Sicilia mai, ne ho mangiato mai il vero stufato Siciliano di pesce), ma era molto buono.