Our toddler has been obsessing over the story of The Gingerbread Man recently. So it seemed only right that we started making actual gingerbread men together.

Now, every time he grabs the book for me to read, he points at the gingerbread man on the cover and says, “We make some buttons!” Handling the mixture, rolling out a soft-ish dough, doing the cutting and transferring the pieces to a baking sheet aren’t exactly jobs for a two-year-old (see previous post), but he’s very happy to be given the task of sticking currants in to make eyes and buttons. Nothing fancy. No icing decorations. It isn’t Bake Off, it’s just father-son “do making”, making something he then ardently scoffs whenever we allow.

Cake and biscuit

Gingerbread is a fairly generic name that covers both soft cakes and a cookies, but I’m talking about those distinguished in the UK and US traditions from other ginger cookies by being cut into the shape of a man. One source on Wikipedia says they were first recorded as being made in England for the court of Elizabeth I, who reigned 1558-1603. Though ‘breads’ sweetened with honey and spices are quintessential foods for feast days and celebrations and have probably been made in Europe since the Middle Ages, if not longer.

Various ginger-spiced biscuits and cakes can be found in the traditional feast day foods of much of Europe still, but notably in Britain, Germany (eg lebkuchen), Scandinavia, the Netherlands, Poland etc: that is, more northerly countries. It’s easy to imagine Medieval folks huddling round fires in the winter and very much appreciating feast day treats containing ginger, cloves etc, as such spices have a warming effect.

Sentient food

Now, before I get to a recipe, I must talk a little about the story The Gingerbread Man. I love folk stories, fairytales, Märchen. I’ve read a lot, and I look forward to the kids being old enough for me to introduce more to them. I know full well they can be illogical, macabre and confounding to the modern mind, but The Gingerbread Man is downright weird.

Here’s the gist, if you don’t know it, or need reminding. A childless couple (which obviously resonates) decide the way to overcome their sadness isn’t to, you know, visit an orphanage, but instead to bring forth life through the medium of baking. Indulging in some kind of dough-based witchcraft. I suppose it’s not unlike Gepetto carving a son out of a piece of wood in Pinocchio.

The old lady makes a gingerbread man. But rather than being a dutiful son, he leaps out of the oven, out the door, and runs off. The old woman and her husband give chase. Various other people and animals see him and join the chase. The couple want their “son” back, the others want to eat him – despite him being ambulatory and self-aware, as evinced by his taunting song: “Run, run, as fast as you can, you can’t catch me I’m the gingerbread man!”

When he reaches a river, a fox appears and offers to carry the gingerbread man across. The sentient – but none-too-bright – biscuit agrees. But the fox tricks him and in three tosses of his head, he eats him all up. Snap! Snap! Snap! And that’s the end of the gingerbread man.

The moral of the story? Who knows. Maybe it doesn’t have one. It’s suggested that folk stories teach children about life, but it’s not always clear what the lesson is. The lesson here is not to be gullible or trusting of strangers, I suppose. Or alternatively to beware hubris. Certainly, the gingerbread man is a proud fool. Arguably the hero of the story is, instead, the fox. He’s cunning, and gets the snack. Cunning is quality in many cultures (eg the Italian concept of furbismo, which kept Berlusconi in power for so long), and is often exemplified by the fox, an archetypical trickster, in folk stories.

There are other folk stories about runaway food in British, German and Easter European folklore – balls of dough, pancakes, bannocks – but the gingerbread man story appears to be a variation that evolved with migrants who settled in America.

Melt or rub

Whatever the origins or moral of the story, the boy loves it. Finding a recipe we could easily make together has been a minor challenge. Pre-children, I probably would have tried half a dozen recipes, but today, with two under-threes, I tried just three recipes. One from Dan Lepard’s Short and Sweet, one from Leith’s Book of Baking by Prue Leith and Caroline Waldegrave and one from Geraldene Holt’s Cake Stall (a hand-me-down from my mum with a wonderful dated 1980s cover, where Holt looks like an Edwardian).

The two main approaches for making gingerbread men involve melting together butter and sugar, then combining with flour etc, or rubbing the butter into the flour, and adding the sugar etc. The latter is easier, but frankly, the best one of the three I tried was Leith one, which involved melting. The dough was trickiest to handle, but the resulting cookies had a proper snap – suitably enough considering the gingerbread man’s fate in the jaws of the fox.

Making the dough (or paste), then cooling it in the fridge to firm it up and relax the proteins isn’t exactly ideal if you have a small child chomping at the bit to “do making” right now! I tried to lull young T-rex by putting The Jungle Book on (it was a rainy day) but it still wasn’t ideal. So I suggest making a batch of the dough in advance, then freezing some or leaving it in the fridge until the optimal “do making” moment in your day.

Recipe

This is based on the Leith version, but tweaked somewhat.

If you’re doing this with a small child, make the dough in advance to give it time to cool, so you can do the rolling, cutting and baking in one hit.

225g unsalted butter

200g caster sugar

160g soft dark brown sugar

350g plain flour

6g baking powder

3g fine sea salt

3g ground cloves

12g ground ginger

2 eggs, beaten (that is, about 110g beaten egg)

1. Melt together the butter and both sugars, stirring and cooking until the sugar has all dissolved.

2. Take off the heat, allow to cool slightly, then beat in the egg.

3. Sieve together the flour, baking powder, spices and salt.

4. Put the sieved mixture into a bowl then gradually add the butter, sugar and egg mix, combining to form a homogenous mixture.

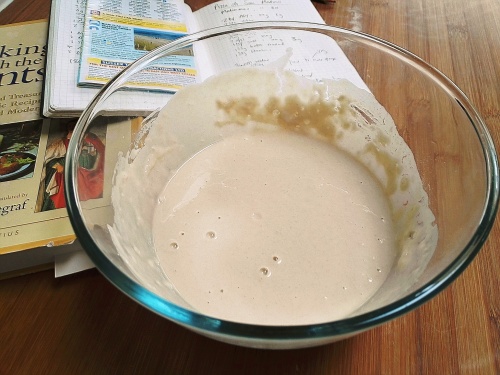

5. It’s a very soft dough, so put the bowl in the fridge to cool it completely. Then you can divide the mixture into slabs, and keep one in the fridge for a day or so until you want to do the baking. You can also freeze it.

6. When you’re ready to roll, heat the oven to 180C and line baking sheets with parchment or silicone.

7. This dough warms up easily and gets soft, so to cut out the gingerbread men, do it in portions. Roll to about 4-5mm thick and cut out your men. We have a cutter about 13cm tall by 8cm armspan. Decorate with currants for eyes and buttons if you like.

8. Place on baking sheets lined with parchment or silicone, with enough room for some spread, and put in the oven. Note, this dough will spread slightly, especially if you’re oven isn’t quite hot enough. (What the knobs says and the actual temperature inside are very likely to not be the same if you have a domestic oven, so I recommend an oven thermometer.)

9. Bake for about 10-12 minutes until nicely brown. Leave to firm up on the tray for a few minutes then transfer to cooling racks and allow to cool completely. They should crisp up as they cool.

10. Satisfy the obsession of toddler. Briefly.

This is, obviously, a tricky area. I love to bake; he loves sugar; I try to be a responsible parent and not allow him too much. I want to nurture a sane relationship with food, where sweets are treats. This is a challenge as refined sugar is so addictive small children rapidly get crazy for it, something that’s exploited by the food industry and insufficiently regulated. Just look at breakfast cereals, some are a third sugar or more. But that’s another story, another rant. Run, run as fast as you can, I’m a two-year-old on a sugar rush….